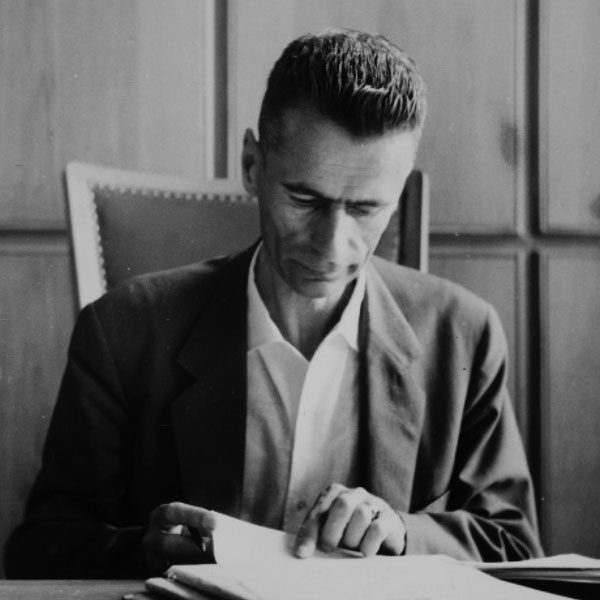

Silvius Magnago

(1914 – 2010)

“The best autonomy is of no use to us unless there exists the will to survive, to assert one’s identity, one’s culture and one’s language. This has nothing to do with nationalism.”

Silvius Magnago, 1992

Listen in Italian | duration 3 min

Listen in German | duration 3 min

The family

The father

His father, also Silvio, was from an Italian family in Rovereto in Trentino. Pro-Austrian, he studied law in Innsbruck and became a fully bilingual judge in Meran.

The mother

Helene Redler came from Bregenz in Austria: her father and later her brother were active in local politics in the province of Vorarlberg.

Little Silvius

He was born on 5 February 1914, a brother between two sisters: Maria (1913) and Selma (1917). Just half a year after Silvius is born, the First World War begins.

The great love

Il grande amore

In Rome Silvius Magnago meets his future wife, Sofia Cornelissen from Essen in Germany.

Marriage

In 1943 he celebrates his wedding to Sofia Cornelissen in Innsbruck. After a few days he returns to the front in the Ukraine.

Childhood

World War I

The family experiences the end of the war in Bozen. The worst seems to be over, but a great disappointment is to come:

South Tyrol is no longer part of Austria. Father Silvio becomes an official in the Italian judiciary.

Fascism

Like all former Austrian officials, the father is kept under careful watch by the authorities. His children have to switch to an Italian school in 1923, earlier than others.

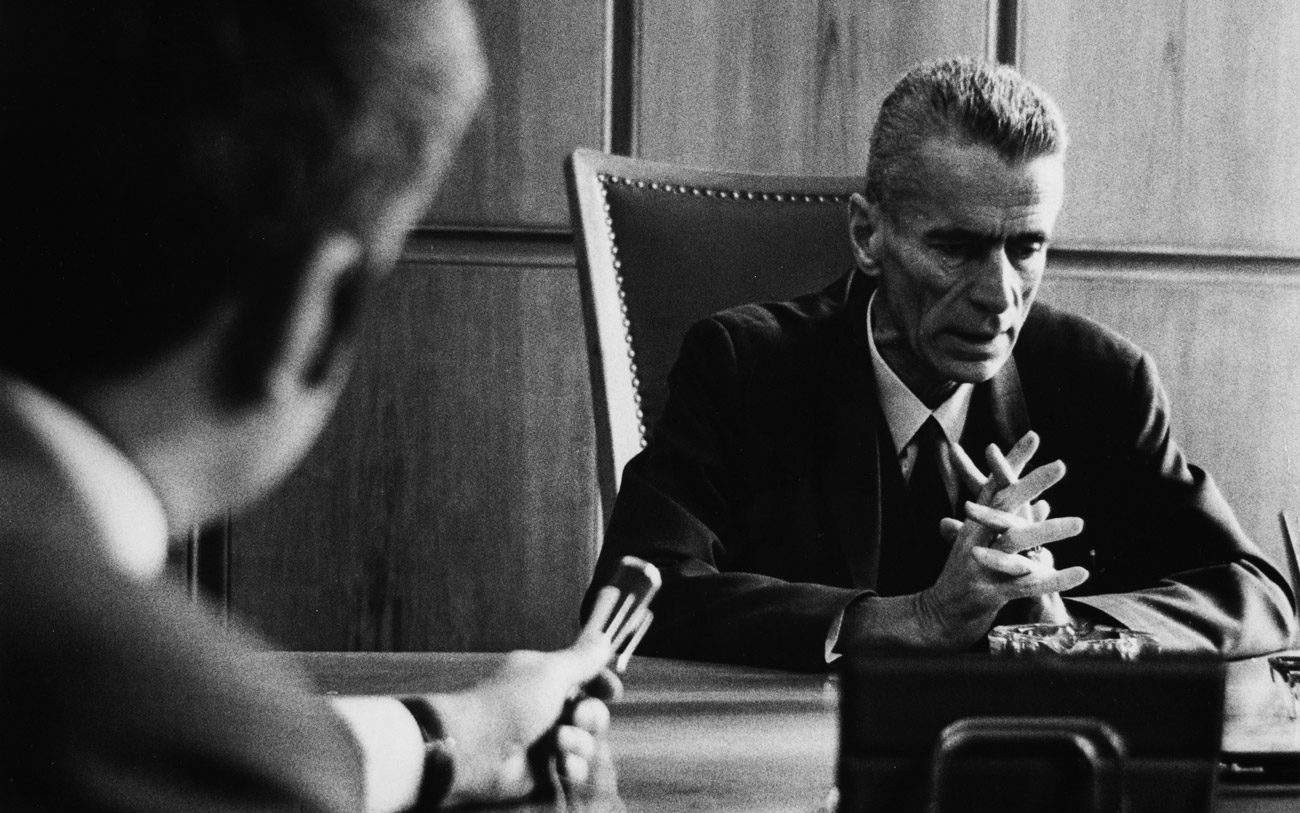

The negotiations

The negotiations

It is not until 1961 that the Italian state is ready to negotiate new arrangements for autonomy. Every paragraph and comma is debated until the so-called “Paket” (package) is sealed. A crucial factor in the success is the high opinion of Silvius Magnago held by Aldo Moro, Prime Minister of Italy from 1963 to 1968, who says: “We can trust this man.”

The package

In 1969 the SVP decides on the “package” at its party congress. Magnago must use all of his authority to get a majority for his efforts. Only 52.8 % vote “yes”.

Education

Education

After high school he studies law in Bologna, which is interrupted by military service. His university thesis is a comparison of German and Italian racial laws.

In the army

Thanks to his height, 1.86 metres, he is made a lieutenant in a parade regiment in Rome. His functions include duty at Hitler’s state visit in May 1938.

War

The “Option”

In 1939 the people of South Tyrol have to decide whether to emigrate to the German Reich, or to stay and renounce all rights as a minority. Magnago opts for Germany “in protest against Fascist rule”.

His leg

Two months after his wedding, his left leg is hit by a grenade during fighting in the Ukraine, leading to amputation. From then on he suffers constant phantom pain.

The Nazi era

From 1940 to 1942 he works in in the office of the Nazi authorities in Bozen tasked with handling the resettlement programme. Magnago is entitled to be deemed “indispensable”, meaning he would not be sent to the front. He rejects this, however.

Last years

of work

Everyday life

The second Autonomy Statute enters into force in 1972, but negotiations on the details with Rome continue. At the same time, the region experiences a wave of prosperity. Shown here is the opening of a new kindergarten.

The awards

Austria and Germany confer numerous high awards upon Magnago for his life’s work. He accepts the Italian order of the Cavaliere di Gran Croce much later – long after Italy and Austria in 1992 officially end their dispute over South Tyrol, which had come before the UN.

Farewell

After 29 years, on 17 March 1989 Silvius Magnago completes his last working day as Governor of South Tyrol. He will continue as leader of the South Tyrolean People’s Party until 1991.

Politics

Into politics

In 1948, a symbol of a war-torn generation, he fights the first election campaigns for the South Tyrolean People’s Party (SVP). He is immediately appointed deputy mayor of Bozen and, alternately, president of the local parliament and the regional council.

The demonstration

In 1957 Silvius Magnago becomes chairman of the SVP. Supported by the hard-line wing of his party, he calls for a rally at Sigmundskron Castle to protest against Italy’s approach to South Tyrol. Some 35,000 demonstrators attend and demand autonomy for South Tyrol.

The attacks

Peaceful protests are followed by attacks on symbols of the Italian state. These reach an initial climax with the “Night of Fire” when, on 12 June 1961 – Magnago has recently also been appointed provincial governor – explosives are detonated under some 40 electricity masts. The aim, to draw international attention to South Tyrol, comes at a high price: an increased military presence, arrests, maltreatment. The attacks continue, this time causing deaths.