The road

to autonomy

Has South Tyrol achieved the best possible results with its autonomy? Or could more have been obtained?

What is certain is that the road to autonomy has been long, often with higher interests in play, with setbacks and even suffering. That the road would lead to peace was far from self-evident.

Timeline

The Peace Treaty of Saint-Germain

The peace treaty at the end of the First World War seals the division of Tyrol and the transfer of the southern part to Italy. South Tyrol hopes in vain for self-determination or autonomy.

The March on Rome

Fascists march on Rome as their leader, Benito Mussolini, takes over the government. Fascism comes to power in Italy. It oppresses linguistic minorities and promotes immigration from other regions with the aim of full Italianisation of the “new provinces”.

The option

Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany present the German and Ladin-speaking populations of South Tyrol with a choice: emigrate to the German Reich or remain in Italy, but without any protection for minorities. More than 85 % opt for Germany: some 70,000 emigrate between 1940 and 1943.

Allies occupy part of Italian territory

The Allies invade southern Italy. On 8 September 1943, following the fall of Mussolini, a new government in Rome signs the act of surrender. The German Wehrmacht occupies northern Italy and declares the provinces of Bozen, Trento and Belluno to be its Operational Zone of the Alpine Foothills.

A new phase

The end of the Second World War permits a new, democratic beginning. On 8 May 1945 the Allies approve the establishment of the South Tyrolean People’s Party (SVP) and recognise it as representing the German and Ladin-speaking communities in South Tyrol.

The Paris Agreement

First Autonomy statute

Autonomy disregarded

Silvius Magnago becomes chairman of the SVP

The event at Castel Firmiano

Sigmundskron Castle sees 35,000 people come to a rally organised by the SVP under pressure from the party rebel, Hans Dietl. The demonstrators call for autonomy for the province of Bozen and accuse Rome of furthering the migration of Italians into South Tyrol.

The UN resolution

The new Austrian Foreign Minister, Bruno Kreisky, succeeds in bringing the South Tyrol problem to the UN, which calls on Italy and Austria to solve the problem together: initial negotiations offer little hope of success.

The Commission of the Nineteen

The Italian government sets up the so-called Commission of Nineteen (11 Italian speakers, 7 German speakers, 1 Ladin speaker). After three years they submit a first draft for a new autonomy statute: autonomy is to be transferred to the two provinces of Bozen and Trento.

The Night of Fire

It is the climax of a long series of attacks that had begun in 1956. The perpetrator of the attack is the separatist group BAS Befreiungsausschuss Südtirol (Liberation Committee for South Tyrol). “The Night of the Fires” draws the attention of Italian and European public opinion to South Tyrol.

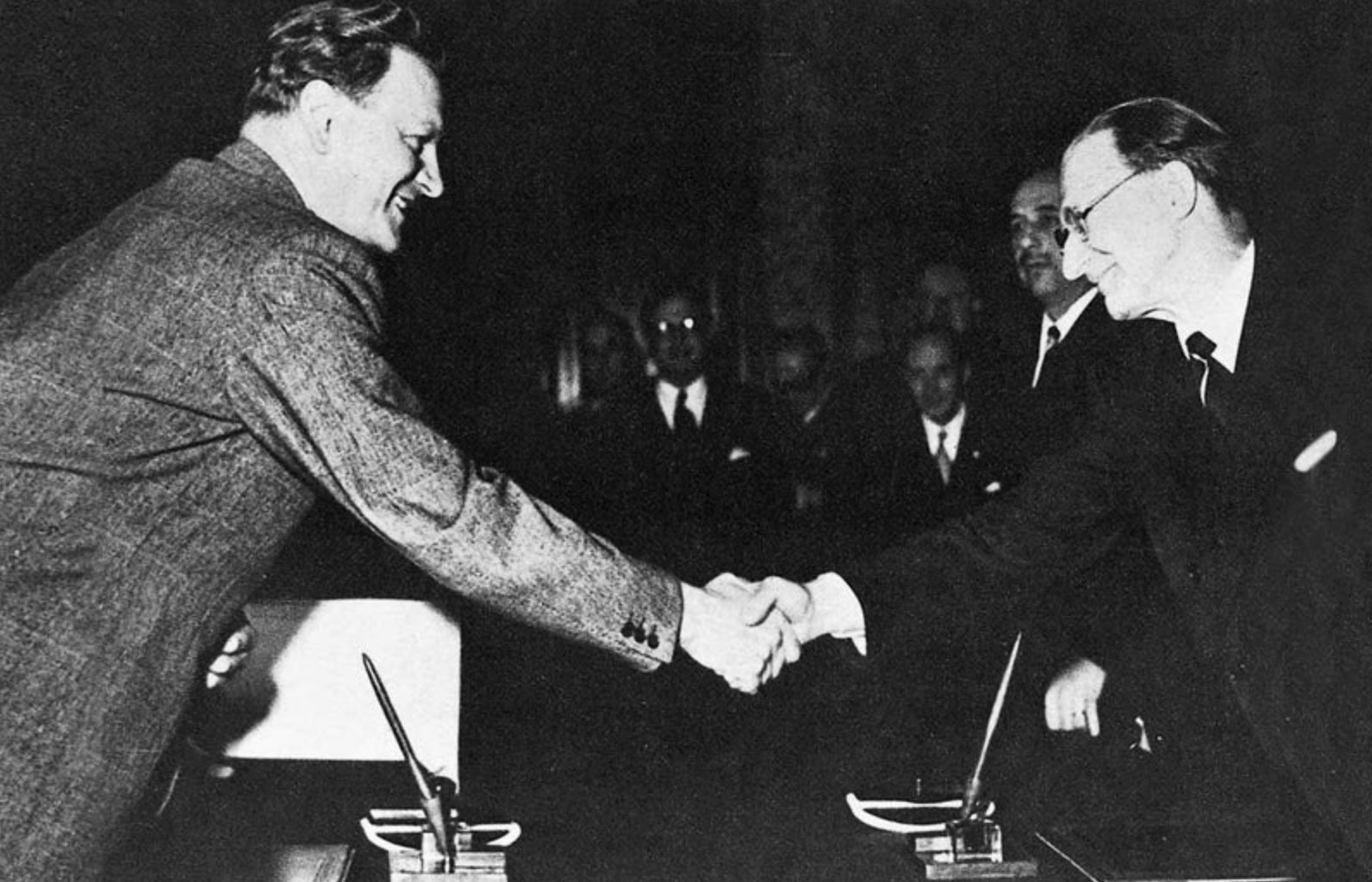

Yes to the Package

After lengthy negotiation, Italy, Austria and a small group led by Silvius Magnago all agree on a “Paket” (package) of measures to be implemented according to an Operation Calendar. The SVP only accepts this package by a narrow majority.

The second Autonomy Statute

The second Autonomy Statute enters into force. Many details are yet to be clarified by the so-called Commission of Six over the following years, with both supporters and opponents working together. Key figures include Alcide Berloffa, Roland Riz and Alfons Benedikter.

Alcide Bwerloffa becomes chariman of the Commission of Six and the Commission of Twelve

Acquittance release

The Italian Government adopts the latest provisions in the “package”. Italy and Austria report to the UN that the long-standing international dispute over South Tyrol has been settled. Negotiations between South Tyrol and Rome on “dynamic” autonomy however continue.